Ron Mordechai Makleff (presented at IMC Leeds 2022)

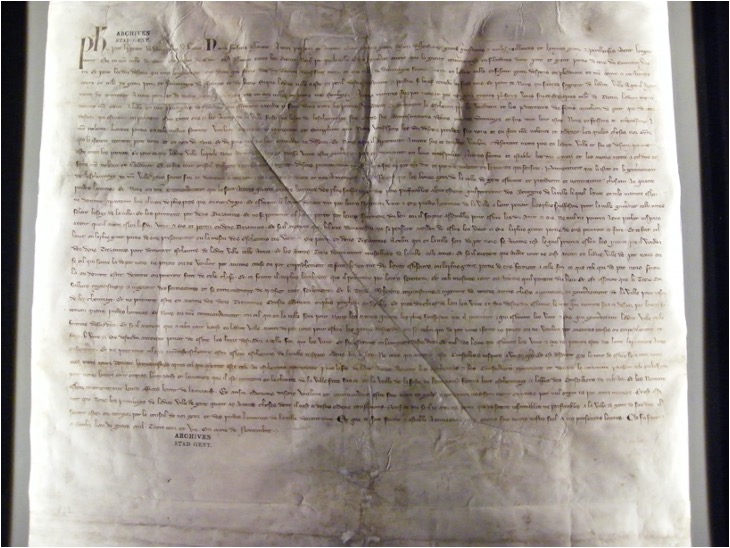

There is a common trope in recent material histories of documentary culture of the Middle Ages that asks us to remember that documents were objects, that they had a physical aura of power. When a petition to the King of Castile was answered with a document delivered via royal messenger, the recipients would do a certain dance with the document held on top of the head; when a charter was held up during a judicial proceeding, a protest march or a city council meeting, its presence was felt even – perhaps especially – for those who were unable to read it; when the count of Flanders won a 1328 victory defeating the armies of an urban-rural coalition that had held the county for nearly six years, the submitting burghers knelt before the church steps, where their new charter of privileges was held aloft from a tower (see the image in the top margin below). :

Similar ceremonies were immensely symbolic, and the symbolism was lasting. Even three hundred years later, similar episodes are seen in the submission of the provinces of the Low Countries to the Duke of Alba.

All this is to say that documents as objects, especially with the visible authentication provided by a seal, were crucial parts of medieval ceremonies of information. Historians love these episodes, perhaps because they spend too much time sitting in dusty rooms with the documents in question; it is affirming, sifting through archives, that someone used to care about the piece of parchment you’ve been staring at for hours. But resisting the temptation to fetishize archives – real story [show Wimmer’s book] – pays off. Documents had afterlives: copying, destruction, summation, cancellation, registration – all activities that impact in one way or another how and whether the document has been passed down to us, and by whom. In other words, what if the contents of the document itself – while important – are no more significant than the mere fact and nature of its survival as a source? Once we’ve imagined the document as a presence, we can also consider it as an absence.

I am inventing little here! There is work on Überlieferungschancen, the rate at which certain texts survived across the centuries into our own sourcebooks and archives; typically a quantitative affair. But Paul Bertrand has recently shown how much context and specificity mattered to the survival of a specific type of document. Let’s use the urban charter of privileges as our example. Generally there has been agreement that these charters of privilege recorded in writing some fundamental liberties and powers for urban and rural communities.

Charters of privilege have seemed the most tangible record of urban autonomy and power, but as we see here, they were also targets of violence. How, nonetheless, do charters of privilege survive in such numbers? what kinds of traditions of copying and confirming were they subjected to? What did the prevailing administrative and scribal tendencies mean for the way they survived?

The afterlives of charters of privilege as political objects becomes particularly contentious, as far as we can tell, a few hundred years after they take the stage in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Let’s first explore the preservation and memorialization of urban charters of privileges, primarily from the Low Countries in the fourteenth century, at two crucial junctures, one in the early fifteenth century and the other in the middle of the nineteenth (starting with the latter and generally moving backwards in time).

Then, we’ll take a look at a few unique sources from each period that provide clues about the material afterlives of charters of privilege in their political context, alongside other types of documents. Ι hope these will illuminate a few of the statist, teleological, and hierarchical assumptions inherent to this privileging of “the privilege.”

Finally, I will explain what I see as anarchist about this methodology, and why, as Ian Forrest almost suggested in his recent article in Anarchist Studies, I think many medievalists might actually already be anarchists.

To do so, we’ll look at a corpus of alternative legitimacy granting documents, charters or letters of urban alliance, mostly from the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Low Countries, to illustrate.

For centuries probably the best-studied sources for European medieval urban history have been sealed charters issued by princes delineating what are variably known as the exemptions, rights, liberties, franchises, or, most often in English, privileges of a town.

Often large, physically imposing parchment documents, these were issued in large numbers during a long twelfth century stretching from 1050 to 1250, 500 charters of associative privilege survive from between the Ebro and the Rhine alone. The truth is that their contents are too varied to categorize – jurisdictional and fiscal rights; exemptions from certain taxes or fees; mechanisms for electing municipal officials; power-sharing agreements of many other kinds.

Historians have studied these charters to a variety of ends. Thomas Bisson suggests that these charters were issued by princes in response to the violence of castellans and other agents of the regime itself, as a way to minimize “exploitative lordship.” Rulers “feasted on the violence their peoples suffered” at the hands of minor feudal lords as a means of justifying the extension of their own governing power, symbolized by the charter of privileges granting communities written recourse to the collection of exemptions and guarantees included. Several generations earlier, charters of privilege were the key evidence for historians that ascribed the accumulation of urban rights to a “communal movement” that was at turns bourgeois, popular, or proto-national – depending on the loyalties of the historian studying them. Practically all of these found that the lordly charter of privileges was fundamental to the execution of power and the rituals of communal politics alike in the late medieval European town.

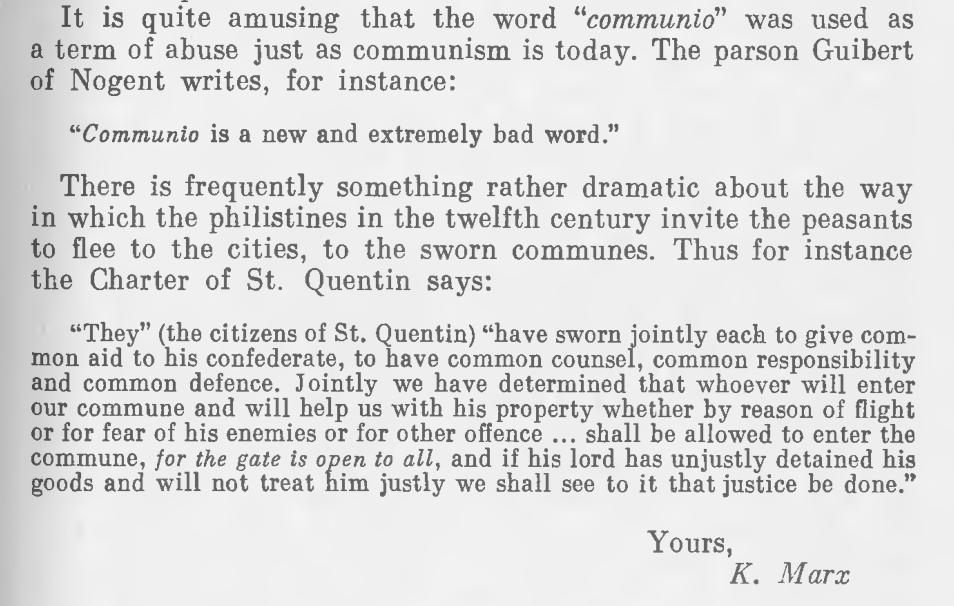

When Karl Marx argued in a 1854 letter to Engels that “the communal movement of the late Middle Ages” emancipated townsmen from the feudal structure, he was searching for compatriots from the past more than he was learning about the origins of capitalism (which, at least in the historical analysis of Capital vol 1, he found largely in economic relations in the countryside). Today, we know through the work, among others, of Achille Luchaire and Andrea Gamberini, that cities were part and parcel of the feudal structure, that they were a form of communal lordship. But remember that Marx’s research consisted of reading Augustin Thierry’s recently published Recueil des monuments inédits de l’histoire du Tiers État (1853). Marx comes off as preachy in the letter to Engels (“Had Mr Thierry read our stuff, he would know… ”). His takeaway? “What [Thierry] successfully elaborates and underlines is the conspiratorial and revolutionary nature of the municipal movement in the twelfth century… It’s funny how the word ‘communio’ is often reviled in just the same way as communism nowadays,” he writes, quoting Guibert of Nogent.

Much like Marx, Thierry, too, arrived at the field of history for what we might call ideological reasons: his project, under Minister Guizot (1787-1874), was to build a learned “monument du Tiers-État.” He focused his case study on the northern department, “the sole pays with a remnant of the provincial and communal spirit” and it was the first place he began searching for archival traces in 1837 (see Gerson).

By a monument to the third estate, Thierry meant both the bourgeoisie of the ancien regime he was writing about through urban charters of privilege and the bourgeoisie that powered the July Monarchy of Louis Napoleon (who was paying his own salary). Thierry had become an historian in the 1810s, he tells us, because he thought it might open up “an arsenal of new weapons for use in the polemic against the reactionary tendencies of the government.” Thierry was not alone. For hundreds of regional, national, and municipal voluntary associations of amateur and professional historians, publishing selections from archives was an obvious way of promoting their understandings of the past, and their politics (one needs read no further than the introductory materials in the thousands of archival inventories published in the nineteenth century). We are all too familiar with the value judgments of these past archivists: documents of no value, nothing of interest, unremarkable, etc. The publication of archival inventories was (and is) at least as much about the present as about the past: what was left out and what was included.

To give just one striking example, a mémoire historique introducing the inventory of the medieval archive of the city of Mechelen (1859) writes that “the nation manifests itself these most authentic and most numerous documents.” It is followed by a lengthy list of all the members of the communal administration in that year. The same decade.

Even for Peter Kropotkin, who did more than anybody (save perhaps Otto von Gierke) in the nineteenth century to promote the idea that towns could be robust self-governed institutions, the charter of privileges tended to be a monument to urban power rather than submission to princely regimes of authentication, certification, or legitimation.

Urban communities in the High Middle Ages, he wrote, “free themselves from their lord’s yoke, and slowly elaborated the future city organization” and elsewhere, referring to charters of privilege: “Hundreds of charters in which the cities inscribed their liberation have reached us.” This process of liberation was true for some regions, but the underlying assumption of nineteenth-century thinkers that medieval towns needed to liberate themselves from rulers rather than fight off encroachments from them is telling, and symptomatic of many analyses from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries as well. As Susan Reynolds reminds us: “Perhaps communities were always there, in the sense that groups of people acted together over long periods, and took their mutual responsibilities and solidarities largely for granted.” Only later would they create documents to that effect.

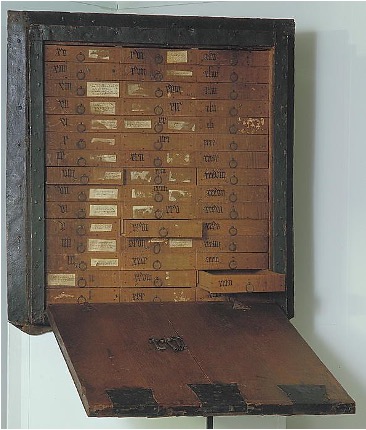

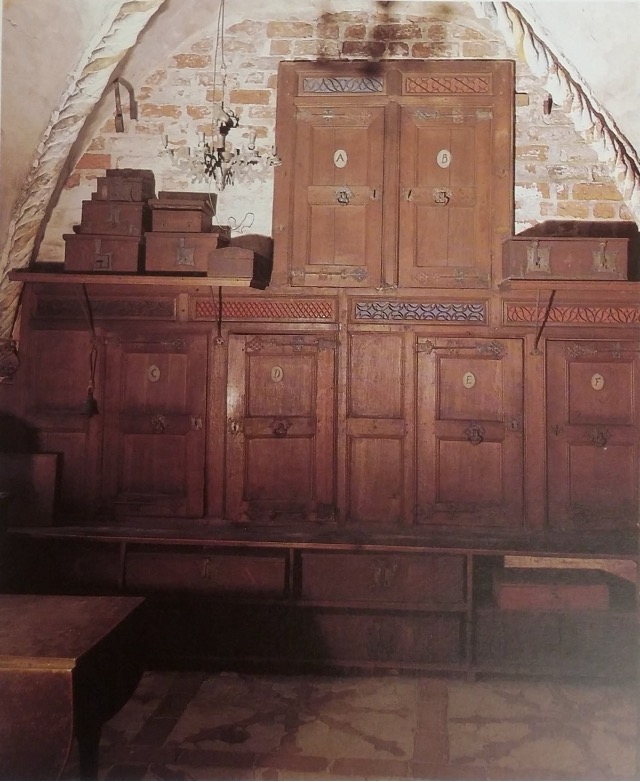

Urban charters of privilege survive in huge numbers from the twelfth century on. Indeed, they were celebrated and given literal pride of place in municipal archival arrangements. The best case study I’m aware of is that of Ghent. For very relevant reasons I don’t have time to go into here, the case of Ghent is quite unique: the terms of the Treaty of Tournai in 1385 meant its archive would survive the 1380s uptick in anti-seigneurial rebellion across northwestern Europe. But notice also that, alongside dozens of charters, there are also letters of alliance in 5 of the 18 trays described in the table of contents (F, S, T, G, and L).

This is one of the most detailed pieces of evidence we have for municipal archival practices in the late medieval Low Countries, a glimpse at the incredible creativity and diversity of lay documentary culture at the time. For Bertrand, what determined whether a document would be kept was mainly a product of its “forseeable obsolescence” aka the type of document it was and its ongoing usefulness. In an adaptation of Brian Stock’s concept of “textual communities,” and extending her own work on urban seals, Brigitte Bedos-Rezak has shown that cities had their own ‘civic liturgies’ surrounding municipal archiving.

In case after case, northern French towns can be seen thirsting for copies, confirmations, renewals of their privileges from lords. In this way, at least the urban patriciate – or whatever political coalition was able to achieve hegemonic status within the town – was able to secure its position. The charter of privileges was effectively the documentary expression of a hierarchical order that rulers increasingly sought to promote, not the least important feature of which was making themselves a necessary dispenser of legitimacy in the form of these very charters. This engrained a hierarchical relationship between lords and communities. But this craze for certified copies of privileges, Bertrand reminds us, was rampant not only for towns but also mendicant houses and other localized forms of lordship, and in guilds and other voluntary associations. It can be traced in the genre of ‘vidimus’ which had a real moment in the fourteenth century. Preservation was political.

So It makes sense to see the charter of privileges as one among a whole series of documentary experiments in conjuring authority out of parchment and wax, and it had a particularly powerful set of associations, eg imperial Urkunden and papal bulls. The question of survival is already quite different.

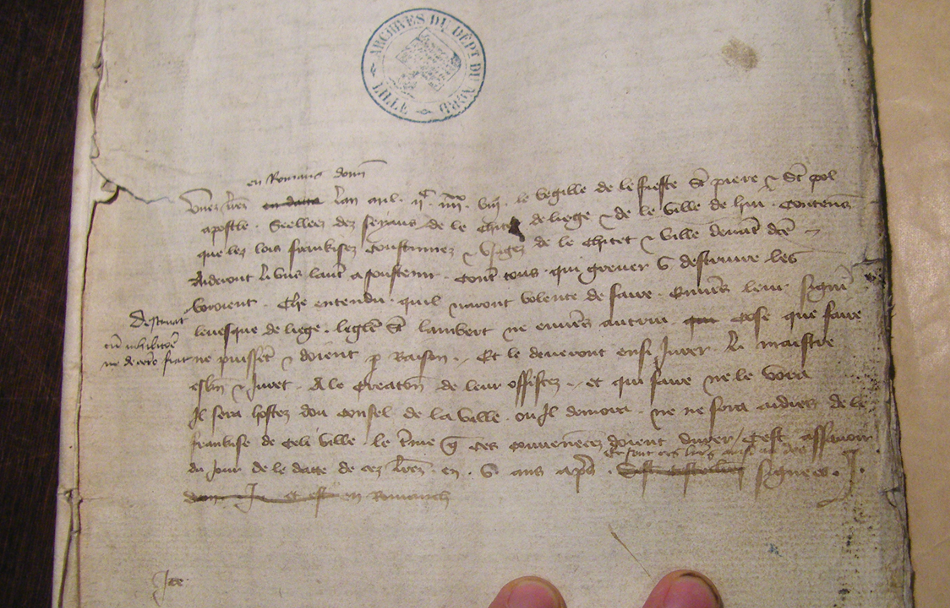

An incredibly well-documented example comes in the aftermath of the Battle of Otheé in 1408, when a coalition of Liégeois towns known as the hédroits rejected the regime of their prince-bishop and ejected him from the bishopric for several years. Several of the Low Countries most powerful princes joined forces to fight against this urban alliance. Inscribed in the margins of the series of inventories created by their archivists and scribes in 1409, is shorthand for the fate of the towns’ documents “R” for restituatur (return) or a “D” for destruatur (destroy). If the inventories are correct, 142 charters were returned and 440 were destroyed. This was part of a series of episodes, all recorded and in a specific ritual sequence, from defeat to confiscation, triage, and return. These were the documentary stages of the ritual process of submission.

What was confiscated? Overwhelmingly, Charters of privilege were returned. Just as overwhelmingly, letters of alliance were destroyed. The main point here is that – at least in this particular corner of the Low Countries in the late middle ages – archiving became incredibly contentious, and the corpus of inter-urban alliance letters is a striking example of how a ubiquitous type of medieval document becomes a rarity.

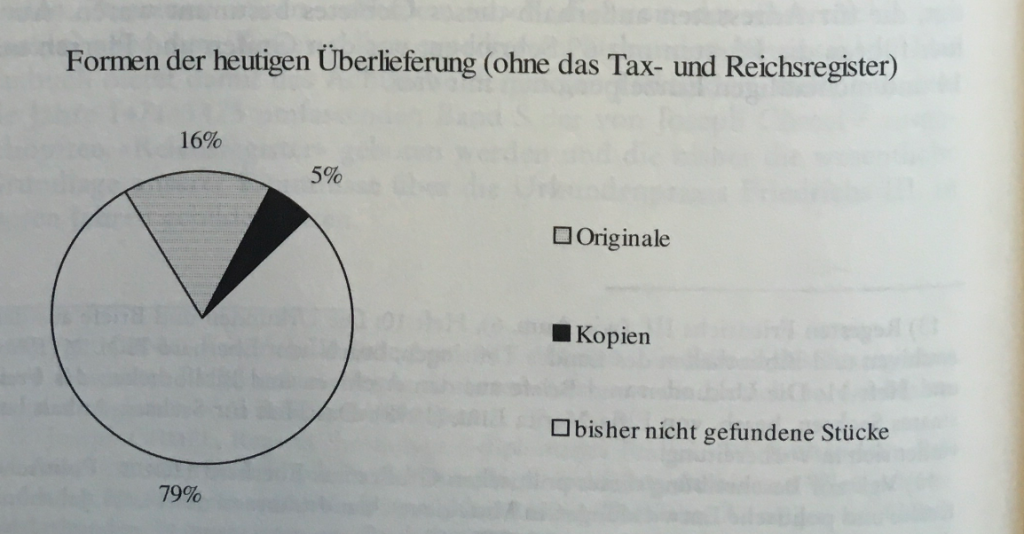

What were these alliances? By way of an example, the alliance of 1262 in Brabant was designed to suppress inter-urban worker revolts, but others have very different nature. This is a relatively rare example, but I have tracked down records (many originals) of 145 iterations between 1219 and 1445, though there are up to 50 copies of a single alliance because they were composed of many bilateral agreements. Compare this to the number of extant privileges? Just the half century between 1201 and 1249 yields 23 in one online database known as Diplomata Belgica. Their number may at some point have been comparable.

The point is that the historical record has been indelibly shaped by the late medieval administrators who created the princely archives of their times, in ways that resonate and exaggerate the tendencies of the nineteenth century sourcebook.

In other words, the charter was naturalized as the form of urban authority, but that may have come as quite a surprise to medieval townspeople, who at times saw alliances as completely legitimate means of pursuing their own authority under a kind of self-legitimation.

At nearly every possible juncture over the course of seven centuries, privilege was given pride of place in the formation of institutional and historical memory. An anarchist methodology, moreover, can only very carefully call upon radical thinkers of the nineteenth century to help us interpret medieval urban politics, so well ensconced were they within the scope and sources of their century’s thought. What Marx’s letter shows so starkly is that he and Thierry are viewing the same processes, but choosing to interpret them in different, often mirrored ways.

In other words, the vocabulary of rights and freedoms we have inherited for thinking about urban charters of privilege already suggests a number of more ideological reasons why these “charters of privilege” have stood at the center of urban histories and thus shaped what insights we might draw about political societies from the past. Indeed, there seems to be a more fundamental methodological blindspot here: legitimation, authentication, and who can provide it. Of course, there are libraries full of scholarship on the significance of urban seals, even work on urban archival practice that emphasizes the centrality of documents to urban community. But why then is the impression still of towns liberating themselves from princes? Perhaps the 1960s-influenced historiography placing street politics in the center of stories about political conflict, in both history and the social sciences is partially to blame. Certainly, historians seem to often interpret as rebellion what could just as easily be considered turbulent interactions between parallel systems of political legitimacy.

This suggests some of what an anarchist methodology can help us learn about past societies; it also reminds us how central the nineteenth century and the emergence of the modern historical discipline, the modern archive, and the modern nation must be considered as an agent in our examination of the medieval past. We must pay heed to the ways in which the compilation of medieval sources under nineteenth-century national methodologies has magnified the processes of consolidation of princely power in the late Middle Ages.

Some sources:

Peter Kropotkin, Mutual Aid

Paul Bertrand, Documenting the Everyday

Augustin Thierry, Le Recoil des monuments de l’histoire du Tiers-État

Stéphane Gerson, The Pride of Place: Local Memories and Political Culture in nineteenth-century France

Samuel K Cohn, Lust for Liberty: Italy, France, and Flanders

Andrea Gamberini, The Clash of Legitimacies

Thomas Bisson, The Crisis of the Twelfth Century

Peter Blickle (ed.), Kommunalismus

Peter Blickle (ed.), Resitance, Representation, and Community

Michel Mollat and Philippe Wolff, The Popular Revolutions of the Late Middle Ages

Leave a comment